As someone who works with vintage Macinti I get contacted occasionally by people who still have files on the hard drives of their old Macs but aren’t sure how to move them to a newer machine. These are typically SCSI-based systems with floppy drives. They might also be early iMacs or other models without FireWire.

Sometimes the old Mac is still working, sometimes not. As long as the hard drive itself isn’t damaged you will be able to get your files but the method will vary.

Sometimes the old Mac is still working, sometimes not. As long as the hard drive itself isn’t damaged you will be able to get your files but the method will vary.

Assuming the old Mac still works and has ethernet, copying across your local network can be the easiest solution. File Sharing will work between Macs as long as they have compatible versions of AppleShare. The older system needs AppleShareIP, which means it must be running Mac OS 8 or higher at least System 7.5.3. For more on how to network across generations, see Vintage Mac Networking and File Exchange.

FTP is another option which works across a wide range of Mac OS versions. Mac OS X has a built in FTP server, which you can enable under System Preferences –> Sharing; turn File Sharing on, then click on the Options… button to enable FTP access. Alternately, you can connect over the Internet to an FTP server you have access to.

FTP is another option which works across a wide range of Mac OS versions. Mac OS X has a built in FTP server, which you can enable under System Preferences –> Sharing; turn File Sharing on, then click on the Options… button to enable FTP access. Alternately, you can connect over the Internet to an FTP server you have access to.

On the old Mac you can use Fetch, Anarchie or other FTP software to post to the server. Versions of these programs go back to the earliest days of Mac System Software and work over ethernet or dialup modems. Good things to have around.

Using the Internet you may also be able to transfer your files with a web browser to a site that has upload/download capability. The limiting factor here is likely to be whether the browser on your old Mac will support this feature – it sometimes requires plugins or versions of Java/Javascript that the old software can’t run. The newest browser you can run on your system is recommended for best results, but its worth a try with whatever you have if necessary. UPDATE: Classilla is a port of the current Firefox web browser and is recommended for Mac OS 9 users trying to get online.

If network transfers aren’t an option Zip disks make a good interchange medium. Internal Zip drives were offered as options on Macs for years, and external drives are available in both SCSI and USB flavors. Simply copy your files to a disk from the old machine, then read them on the newer machine.

If network transfers aren’t an option Zip disks make a good interchange medium. Internal Zip drives were offered as options on Macs for years, and external drives are available in both SCSI and USB flavors. Simply copy your files to a disk from the old machine, then read them on the newer machine.

I’ll bet you or somebody you know has an unused Zip drive in their closet or bottom desk drawer right now!

For Macs that have USB ports (original iMacs, old PowerMacs with USB PCI cards, etc.) you can copy data to a USB hard drive or flash drive for the transfer. However these are likely going to be the original USB 1.1 format which is rather slow, so expect to wait a while (possibly hours) if you have a lot of data.

When none of the above work or if the old Mac won’t start up, and if you feel comfortable working inside your computer, another option is to open up the machine and pull out the internal hard drive. The drive can then be installed in an external enclosure and connected to another Mac.

For SCSI drives you’ll need another SCSI based Mac, preferably one with network access or a Zip drive to serve as a bridge machine. This can be an obstacle unless you have multiple old Macs lying around (or are crazy enough to be a collector…) You can also try using a PCI SCSI card in a PowerMac, or a USB to SCSI adapter (these are a bit rare, but some were made).

Internal IDE drives (G3 iMacs, Beige G3 PowerMacs, etc.) can be installed in external enclosures with FireWire and/or USB ports for direct connection to modern machines. They can also be installed internally in a G3 or G4 tower. Since they are about a decade newer in the Mac timeline IDE drives are typically much easier to work with than SCSI drives, and can often be reused with the newer machine.

Some additional tips thanks to reader feedback:

Dan Knight at Low End Mac writes: You can also transfer up to 1.4 MB of data at a time using floppy disks. All Macs produced since 1989 support high density floppy drives, and external USB floppy drives let you access the disks from your modern Mac. It’s not fast and doesn’t hold a lot of data by modern standards, but it works. Note that USB floppy drives cannot read 800K Mac floppies, they are compatible with high-density Mac and PC floppies, as well as 720K PC floppies.

Steve Lubliner writes: One method to consider to transfer files from older Powerbooks with card slots (e.g. 5300 series) is to use a card slot adapter and a Compact Flash card (or similar memory card). The older Mac files can be transferred to the memory card and the card read by a newer Mac (or PC) with a USB card reader.

—–

The Vintage Mac Museum offers file transfer & conversion services for those who need assistance moving their Macintosh files or converting the data into more current formats.

—–

As many collectors know there’s usually more to a collection than what gets displayed. Space constraints play the largest role, as does redundancy of items and an often seemingly bottomless pile of new stuff to go through. Rarely seen are my systems not on display and the large quantities of spare parts necessary to keep one-to-two-decade old machines running.

The VMM currently takes up all or part of 3 rooms in my house. The displayed collection lives in one of the bedrooms; this contains the working equipment, Mac memorabilia, framed artwork and related items. Room two (shown left) is a small office I’m using as a large storage closet.

The VMM currently takes up all or part of 3 rooms in my house. The displayed collection lives in one of the bedrooms; this contains the working equipment, Mac memorabilia, framed artwork and related items. Room two (shown left) is a small office I’m using as a large storage closet.

In here live many peripherals, books, software and more beige boxes. These include some Macintosh clones (PowerComputing, Motorola Starmax), a PowerMac 6500, a non-working Color Classic, and an original Apple ImageWriter (with ThunderScan). A few drawers hold adapters and cables, and a closet shoe rack makes an excellent storage shelf for hard drives and NuBus/PCI expansion cards. The G4 towers on the floor are awaiting teardown.

Other than a few compact Macs and PowerBooks, I’ve found that space constraints prevent keeping multiple spare systems around intact. With a few exceptions I now tend to keep one working model in good cosmetic condition, and critical items for repairing that system when needed: logic boards, CPU daughtercards, power supplies, screens (for all-in-one systems), floppy drives, hard drives, CD/DVD drives, custom sleds/mounts, interconnect cables, etc.. External cases and leftover mechanical parts get recycled or disposed of. Empty (reassembled) shells from a Mac Plus or SE/30 make good gifts for kids and other Mac geeks.

In a Major Step Forward each model now gets its own shelved box in the attic (photo below) – a MUCH easier system than digging through a bag or box of old stuff and trying to remember if this unlabeled power supply belongs to a IIci or a Quadra. It took a few years but now I should be able to better manage growth via the addition of shelving and boxes. At least, to a point.

There are boxes here for the Mac 512k/Plus, SE/30, IIci/Quadra 840av, 9600 (two boxes), iMac G3, PowerMac G4, PowerBook 170, 540c, 2400c/3400c, Wallstreet, and Pismo. One box contains a Duo 230 which I acquired recently and don’t have room to display at present. You can also see some spare monitors (CRT and LCD), an Apple Color Display “Tilt & Swivel” stand, more Ruby iMacs (I love that color), old Mac carry bags, and several boxes of mice and keyboards. As I acquire more crap I’ll begin to forget what’s even in some of them – then this will truly be a Vintage Mac Attic!

The VMM grows in fits and spurts. Nothing happens for a while, then a bunch of donations occur or a particular model hits the point of “no commercial value” and becomes available in bulk on craigslist or at the local flea market. The PowerMac G4 MDD tower, aka the “Wind Tunnel” Mac, appears to have reached this point.

The PowerMac G4 MDD (Mirrored Drive Doors) was the final iteration of the very successful PowerMac G4 line. Sold in single and dual processor configurations, these were the last Macs which could be dual booted into Mac OS 9 and OS X; newer G4 models and all G5s run OS X only. With 4 hard drive bays, 2 optical drive bays, 4 PCI slots and up to 2GB of RAM capacity, the MDD was Apple’s most expandable Macintosh on the market since the PowerMac 9600.

The PowerMac G4 MDD (Mirrored Drive Doors) was the final iteration of the very successful PowerMac G4 line. Sold in single and dual processor configurations, these were the last Macs which could be dual booted into Mac OS 9 and OS X; newer G4 models and all G5s run OS X only. With 4 hard drive bays, 2 optical drive bays, 4 PCI slots and up to 2GB of RAM capacity, the MDD was Apple’s most expandable Macintosh on the market since the PowerMac 9600.

The MDD tends to run hot, and was the first Apple desktop with variable speed fans. A low whirring sound is always audible, and with fans going full blast the press quickly bestowed the moniker Wind Tunnel Mac. This (acoustic) feature lived on in the even-hotter G5 iMacs and PowerMacs.

I’ve been planning to add a Wind Tunnel to the collection for some time, but until recently the dual-proc models were still selling for several hundred dollars each and I didn’t have a major need. However last week one belonging to a client of mine had a power supply failure, and she decided to upgrade to a new Mac Mini. After assisting her with the setup and data migration, the MDD was donated to the VMM.

Two days later I was browsing my local craigslist and saw an ad for 12 MDD towers (all Dual Proc 1.25GHz) for $700! Turned out to be a batch pulled from a school and being sold via a commercial recycler. I didn’t need a dozen but picked up a pair for $150, and drove up to a warehouse on a rainy Monday afternoon to haul them home. These two models turned out to have some minor problems of their own – each was missing a USB and/or FireWire port – but otherwise they both worked fine.

The next day was the Parts Swap Learning Experience. I used the most cosmetically challenged tower as the sacrificial model. With help from a service manual and some creative tugging (but not breaking) I actually got everything out, and didn’t suffer any cuts or bruises. The cables for the power supply and speaker are definitely not the easiest things to manage, but reinstalling needed parts into the other towers went smoothly.

Still better than servicing a Mac Mini…

And just like that – last week I had no Wind Tunnels, and suddenly I have two with spare parts. I migrated the Vintage Mac Museum website to the new tower, and in the process upgraded from Panther Server 10.3.9 to Tiger Server 10.4.11 – yahoo! The “new” system does actually feel a bit faster, and it’s definitely a few decibels louder than the Graphite G4 tower it replaced.

A Mac Mini Server may come soon, but I’m glad this old friend has finally arrived in the VMM.

In addition to the multitude of Macs in the VMM, I have several items from other Apple product lines which seem to fit the Macintosh Zeitgeist. The Lisa is one such product; the Newton is another.

As many Apple fans know, the Newton was the first Personal Digital Assistant (PDA). The brainchild of then-Apple-CEO John Sculley, the Newton was the grandfather of the Palm Pilot, Blackberry, and eventually – coming full circle – the iPhone and iPod Touch. The Newton MessagePad was the toy to have among the Digital Cognescenti of the 1990s, and remains in (limited) use to this day despite it’s forced euthanasia when Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997.

As many Apple fans know, the Newton was the first Personal Digital Assistant (PDA). The brainchild of then-Apple-CEO John Sculley, the Newton was the grandfather of the Palm Pilot, Blackberry, and eventually – coming full circle – the iPhone and iPod Touch. The Newton MessagePad was the toy to have among the Digital Cognescenti of the 1990s, and remains in (limited) use to this day despite it’s forced euthanasia when Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997.

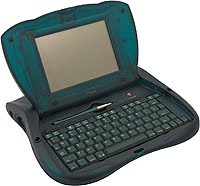

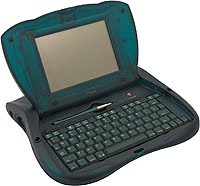

Shortly before its demise, Apple released the Newton eMate, a small laptop (sub-notebook in modern parlance) designed for the education market. Colored Newton green, the eMate had a full Qwerty keyboard, a backlit touch screen (stylus based), an expansion slot, AppleTalk networking capabilities, and a sturdy, appealing design. It ran the Newton OS, not Mac OS, and was a task-based portable computer well suited for note-taking, drawing, record keeping, etc..

The eMate was not a big commercial success, but may not have been on the market long enough to generate sustainable momentum. In my collection the eMate is a perennial crowd favorite, particularly among kids under 10. Children (and many adults) visiting the Museum always gravitate to this system, intuitively understand how to use it, and comment that it’s a cool little computer. Not bad for a nearly 15 year old device! Cell phones of this era usually generate laughter.

It’s industrial design inspired the first generation Apple iBook (but alas, not its color scheme). However like many Apple products, the eMate and the Newton were ahead of their time. I’ve thought about this recently as the iPad makes its debut on the stage – another small portable computer, with keyboard input capabilities, a killer display, wireless networking, a sturdy design, and a task-based operating system. Wonder what it might do this time around?

The “e” in Apple naming schemes resurfaced briefly with the eMac a decade later, another education targeted model, but this has apparently been discontinued (and roundly trounced) by the letter “i”…

One of the things which makes Mac files different from their DOS and UNIX brethren is the inclusion of metadata in the file called “type” and “creator” codes. A part of the Macintosh file system from the very beginning, these two codes convey important information about what kind of document a file is and what program created the file.

One of the things which makes Mac files different from their DOS and UNIX brethren is the inclusion of metadata in the file called “type” and “creator” codes. A part of the Macintosh file system from the very beginning, these two codes convey important information about what kind of document a file is and what program created the file.

The type and creator codes are four character strings, e.g., “TEXT” is a file of type Text. An equivalent kind of type identification is used in most operating systems (including Mac OS X) in the form of a three character extension after the filename, e.g., filename.txt.

The creator code is unique to Macintosh, in that it also tells the OS what program originally created the file: that this text file was created by Microsoft Word and not TeachText. Without a creator code, you can only define the default application to open all files of type “text” regardless of what app created the file. Other apps can still open the file, but the automatic function is limited.

Since OS X replaced OS 9, Apple has supported both type and creator codes, along with filename extensions, in the operating system, allowing either system to be used. As of the release of Snow Leopard Apple now supports primarily filename extensions under a concept they call Uniform Type Identifiers, or UTIs. We will defer to other informative postings about the merits and pitfalls of such a change.

In the Vintage Mac World, type and creator codes are still the way things work. I was recently reminded of this while doing a job to open and convert a batch of MOTU Performer compositions into Standard MIDI files, so they could be opened on a modern computer. Over the years the copies of these files had lost their Mac type and creator codes, and now only appeared as blank, unknown documents to my Mac Plus and copy of Performer.

In the Vintage Mac World, type and creator codes are still the way things work. I was recently reminded of this while doing a job to open and convert a batch of MOTU Performer compositions into Standard MIDI files, so they could be opened on a modern computer. Over the years the copies of these files had lost their Mac type and creator codes, and now only appeared as blank, unknown documents to my Mac Plus and copy of Performer.

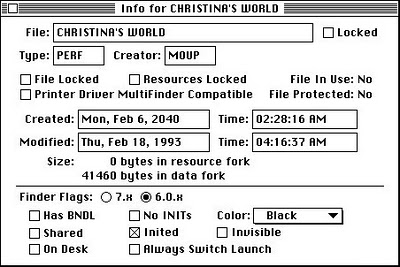

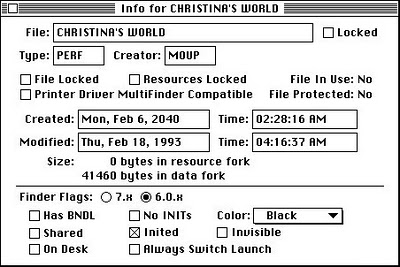

Out of the misty past an old friend comes to the rescue: ResEdit, the “clown jewel” of early Mac geekdom. Specifically an editor for the resource fork of old Mac files — yet another difference between Mac and DOS files, and a topic for another column — the Get Info menu item brings up an edit window where you can set type and creator codes, along with lots of other Important Stuff like whether your file is Invisible or is “Inited” (to this day, I still don’t know what that means…)

I fired up Performer, created a new test file, and saved it to disk. I then did a Get Info on the test file in ResEdit to see what the correct type and creator codes should be: type = PERF and creator = MOUP. With the magic codes I then opened each Performer file individually (no batch conversion in ResEdit) and set the correct info. Once completed they all appeared to the Finder as MOTU Performer documents, and opened in that program when double clicked.

One reason people like the Mac is that “it just works!” Details like type and creator codes are one of the hidden reasons why.

Posted on February 14th, 2010 in

Vintage Mac Museum Blog |

3 Comments »

One of the things I enjoy as a Vintage Mac Collector is getting contacted by people around the country (and beyond) who are looking for new homes for their old Macs. Often several times a month I receive notes such as these:

“Mac friend, I was just about to take a bunch of older Macs to the dumpster or to Goodwill. Are you interested in anything more for your museum? … Thanks for what you’re doing to keep the antique Macs alive.”

“Just cleaning out the top shelf getting ready to move apartments. Do you want this system for your museum: Powerbook Duo 230 … booted it up, happy mac, ran great for about 4 hours last night … I’m amazed at the engineering.”

“Hi Mac Museum, We just found 2 SE/30s in a dusty back closet… they are destined to the trashcan. Is there someone, some org in Hawaii that would want them?”

“Hi I am looking at your website. Do you have any need for the original imac bondi?”

“Interested in a functional 540c? It belonged to me in the mid 90s … I have no need for it now and would like to see something as cool as the Blackbird go to a good home.”

There are many admirable things about passing on or donating old computer to good causes, whatever the platform. Old technology does not necessarily mean obsolete. One man’s trash…

In the Macintosh Community, this feeling is magnified. Old Macs are special, personal, even those we used at work. There was always something notable about being an old Mac user, whether in the original 68k Glory Days<, the Beleagured Apple Computer era, or during the Second Jobs Dynasty. You don't want to just dispose of your old computer, you want it to go to a good home.

In the Macintosh Community, this feeling is magnified. Old Macs are special, personal, even those we used at work. There was always something notable about being an old Mac user, whether in the original 68k Glory Days<, the Beleagured Apple Computer era, or during the Second Jobs Dynasty. You don't want to just dispose of your old computer, you want it to go to a good home.

Mac users go out of their way, often at their own expense, to help make this happen. And I’m pleased, as the Curator of the Vintage Mac Museum, to be able to put some of these Macs to good use. Other destinations may be some of the other Mac Collections Around the World, schools, charities, or a post to your local craigslist.

A special thanks this week to Mark David of Brookline, MA for his generous donation (seen in the photo above) of a Pile O’ Beige Macs. Systems include an LC III, Mac IIci, Quadra 660av, a PowerComputing tower, and a large box of software and accessories. May the Cult of Mac live on…

Sometimes the old Mac is still working, sometimes not. As long as the hard drive itself isn’t damaged you will be able to get your files but the method will vary.

Sometimes the old Mac is still working, sometimes not. As long as the hard drive itself isn’t damaged you will be able to get your files but the method will vary. FTP is another option which works across a wide range of Mac OS versions. Mac OS X has a built in FTP server, which you can enable under System Preferences –> Sharing; turn File Sharing on, then click on the Options… button to enable FTP access. Alternately, you can connect over the Internet to an FTP server you have access to.

FTP is another option which works across a wide range of Mac OS versions. Mac OS X has a built in FTP server, which you can enable under System Preferences –> Sharing; turn File Sharing on, then click on the Options… button to enable FTP access. Alternately, you can connect over the Internet to an FTP server you have access to. If network transfers aren’t an option Zip disks make a good interchange medium. Internal Zip drives were offered as options on Macs for years, and external drives are available in both SCSI and USB flavors. Simply copy your files to a disk from the old machine, then read them on the newer machine.

If network transfers aren’t an option Zip disks make a good interchange medium. Internal Zip drives were offered as options on Macs for years, and external drives are available in both SCSI and USB flavors. Simply copy your files to a disk from the old machine, then read them on the newer machine.

The VMM currently takes up all or part of 3 rooms in my house. The displayed collection lives in one of the bedrooms; this contains the working equipment, Mac memorabilia, framed artwork and related items. Room two (shown left) is a small office I’m using as a large storage closet.

The VMM currently takes up all or part of 3 rooms in my house. The displayed collection lives in one of the bedrooms; this contains the working equipment, Mac memorabilia, framed artwork and related items. Room two (shown left) is a small office I’m using as a large storage closet.

The

The  As many Apple fans know, the Newton was the first Personal Digital Assistant (PDA). The brainchild of then-Apple-CEO John Sculley, the Newton was the grandfather of the Palm Pilot, Blackberry, and eventually – coming full circle – the iPhone and iPod Touch. The Newton MessagePad was

As many Apple fans know, the Newton was the first Personal Digital Assistant (PDA). The brainchild of then-Apple-CEO John Sculley, the Newton was the grandfather of the Palm Pilot, Blackberry, and eventually – coming full circle – the iPhone and iPod Touch. The Newton MessagePad was  One of the things which makes Mac files different from their DOS and UNIX brethren is the inclusion of metadata in the file called “type” and “creator” codes. A part of the Macintosh file system from the very beginning, these two codes convey important information about what kind of document a file is and what program created the file.

One of the things which makes Mac files different from their DOS and UNIX brethren is the inclusion of metadata in the file called “type” and “creator” codes. A part of the Macintosh file system from the very beginning, these two codes convey important information about what kind of document a file is and what program created the file. In the Vintage Mac World, type and creator codes are still the way things work. I was recently reminded of this while doing a job to open and convert a batch of MOTU Performer compositions into Standard MIDI files, so they could be opened on a modern computer. Over the years the copies of these files had lost their Mac type and creator codes, and now only appeared as blank, unknown documents to my Mac Plus and copy of Performer.

In the Vintage Mac World, type and creator codes are still the way things work. I was recently reminded of this while doing a job to open and convert a batch of MOTU Performer compositions into Standard MIDI files, so they could be opened on a modern computer. Over the years the copies of these files had lost their Mac type and creator codes, and now only appeared as blank, unknown documents to my Mac Plus and copy of Performer. In the Macintosh Community, this feeling is magnified. Old Macs are special, personal, even those we used at work. There was always something notable about being an old Mac user, whether in the original 68k Glory Days<, the Beleagured Apple Computer era, or during the Second Jobs Dynasty. You don't want to just dispose of your old computer, you want it to go to a good home.

In the Macintosh Community, this feeling is magnified. Old Macs are special, personal, even those we used at work. There was always something notable about being an old Mac user, whether in the original 68k Glory Days<, the Beleagured Apple Computer era, or during the Second Jobs Dynasty. You don't want to just dispose of your old computer, you want it to go to a good home.