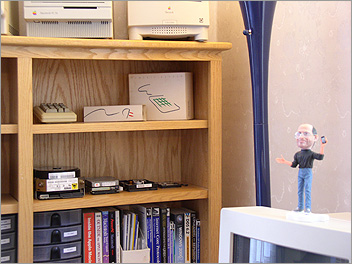

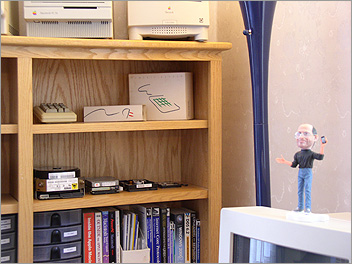

Having a private museum, and one which appeals to a niche audience, it isn’t every day that I give tours to visitors. But I’m happy to accomodate when I can, it’s always fun to meet with people who appreciate the crazy hobby you share.  August 2013 has turned out to be a popular month for vintage Macheads to trek over and check out the collection. And notably, the recent visitors are people who weren’t even born when the Mac made its debut!

August 2013 has turned out to be a popular month for vintage Macheads to trek over and check out the collection. And notably, the recent visitors are people who weren’t even born when the Mac made its debut!

This spring I received an email from a woman looking to setup a tour for her fiance’s 22nd birthday:

“My fiancé has grown up with Macintosh computers and has been fascinated with them ever since he was little. In middle school he realized he wanted to be a Technician and get certified with Apple. I have noticed he has a genuine interest in all products that are Apple and is fascinated with them. I mean, he has even converted me to solely use Apple products!

“I read your FAQ’s, and you had written that you do tours for people who are in/live near the Boston, MA area. I was wondering if you could give my fiancé and I a tour of the Vintage Macs?”

They came by last week and we geeked out for nearly an hour, discussing vintage gear and how to score cheap old Macs (hint: check craigslist regularly). As usual the eMate was an item of interest, as was my QuickTake 150, one of Apple’s early digital cameras.

Then this week, I received another note regarding an even younger Mac fan:

“I am writing to you because I have a young son (nine years old) who is absolutely obsessed with Macs! He is especially interested in all vintage Macs and their operating systems, and is becoming quite the expert. ;) We were hoping to set up a visit to your museum.”

There aren’t many nine year olds who are interested in old Mac operating systems! It’s nice to see the younger generation taking an interest in computing history and legacy. More than once I’ve thought that geeks like myself are becoming our generation’s replacement for classic car enthusiasts, gathering on Sundays with our restored machines to share memories of glory times past.

I hope someday to have a location where I can display the Vintage Mac Museum publicly, for at least limited hours, in order to enable more people to enjoy the collection. Meanwhile if you’re hankering to check out old Macs and you live in or are going to be visiting the Boston area, feel free to drop a line.

I’ve watched enough episodes of Antiques Roadshow and Pawn Stars to know that some items are crossovers, appealing to multiple kinds of collectors. I also spend enough time trolling on eBay for vintage Mac items (and buying more than I should) that I stumble across these myself.  This week the world of doll collectors and Macheads got unexpectedly intertwined.

This week the world of doll collectors and Macheads got unexpectedly intertwined.

In 1996 the Pleasant Company produced this miniature version of a Macintosh Performa to go along with their American Girl of Today line of dolls. Rendered in classic 1990s beige, this adorable little model sports an extended ADB keyboard, the ubiquitous oval mouse, and a faithful rendering of slots and ports on the front and back of the computer. It also comes with a tiny little mousepad!

The CPU takes two AA batteries and is designed to make the Macintosh “chime” sound when switched on. The keyboard and mouse are clickable buttons, and pressing them is designed to display a series of documents and drawings on the screen. Man, these doll accessories are hip! Sadly my model does not work, but it looks great sitting around on top of an Apple HD20 hard drive. I was never a big Performa fan, but this one was just too cute to ignore. A real mini Mac (and not a Mac mini).

And that is how a vintage Macintosh fan purchases an item designed for doll collectors.

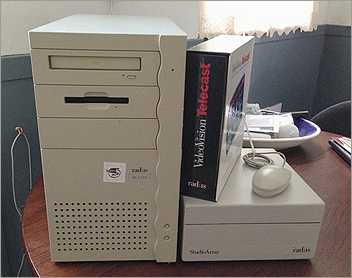

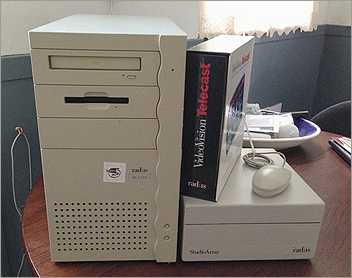

I picked up another old Mac for the Museum this weekend – which I do with reserve these days since space is finite and the models many. However this is an unusual offering, a Radius 81/110 Power Macintosh clone.

For a short time in the mid 1990s, and too long after it would have made a difference in market share, Apple licensed the Mac OS to third party clone manufacturers. The clones were based on Apple supplied motherboards, with value-added features added by the vendors. The group included PowerComputing, Radius, Umax, SuperMac, Daystar, and Motorola – the latter also one of the manufacturers for the PowerPC CPU.

For a short time in the mid 1990s, and too long after it would have made a difference in market share, Apple licensed the Mac OS to third party clone manufacturers. The clones were based on Apple supplied motherboards, with value-added features added by the vendors. The group included PowerComputing, Radius, Umax, SuperMac, Daystar, and Motorola – the latter also one of the manufacturers for the PowerPC CPU.

Apple’s intent was for the clone makers to grow the overall Mac OS market, focusing on the low end. However some of the clones were better bargains and performers than Apple’s own offerings, and they began to sell at the expense of Apple-branded systems. PowerComputing was the most successful of the lot, and their PowerCenter Pro and PowerTower Pro systems were the fastest Macs of the day.

The Radius 81/110 I acquired is a NuBus model, based on the PowerMac 8100 motherboard. This Mac was used for video editing using a proprietary Radius VideoVision editing system, complete with multiple NuBus cards, two outboard rack units, and a whopping 4GB external SCSI RAID. It costs many thousands of dollars when new, and was purchased for $30 at the MIT Flea. But the tower doesn’t work and there’s some major corrosion inside, so I don’t feel too guilty! I love the wave pattern on the front bezel.

Steve Jobs killed the clones when he returned to the company in 1997, buying PowerComputing outright to stop sales cannibalization of Apple’s own models. Motorola was on the verge of releasing a G3 version of their StarMax tower, and had announced the system at MacWorld Boston. The cancellation was costly for everyone, and the resulting impact was often viewed as one reason why Motorola was never able to produce enough fast PowerPC G4 chips for Apple’s use. Coincidentally, Apple switched to IBM exclusively for the PowerPC G5 CPU.

It was definitely an angst-filled chapter of the “Beleagured Apple Computer” era.

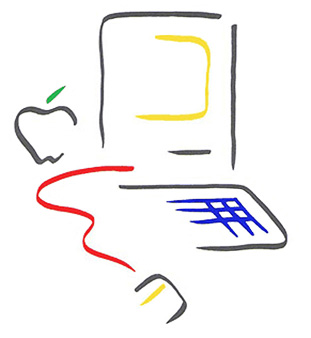

The famous Macintosh Picasso logo was developed for the introduction of the original 128k Mac back in 1984. A minimalist line drawing in the style of Pablo Picasso, this whimsical graphic implied the whole of a computer in a few simple strokes. It was an icon of what was inside the box, and became as famous as the computer it represented.

The logo was designed by Tom Hughes and John Casado, art directors on the Mac development team. Originally the logo was to be a different concept called The Macintosh Spirit by artist Jean-Michel Folon, but before the release Steve Jobs changed his mind and had it replaced by the simple and colorful drawing by Hughes and Casado. It’s been beloved ever since, and the graphic style has endured across decades.

(more…)

Recently I helped a client locate some old QuickTime CD-ROMs from the early 1990s. Back in these days CDs were still fairly new, and people didn’t waste precious storage space on the shiny platters; it was not uncommon to find lots of bonus and filler material on discs of the day. We managed to find three discs, the QuickTime 1.0 and 1.5 releases, along with a copy of the QuickTime 1.0 Beta CD.

My client was primarily interested in the software while I found a search through the bundled materials the most rewarding. I quickly unearthed a few goodies that probably haven’t seen the light of day in over twenty years – which may or may not be a good thing.

The first video, DogCow, was included on the QuickTime 1.0 Beta release CD-ROM. This is a bizarre clip clearly targeted to Apple insiders. Moof, the beloved Apple DogCow from the print dialog boxes, underwent some changes between Systems 6 and 7. The QuickTime team apparently had strong feelings about the event. Either that or they ate too many magic mushrooms…

The second clip is a QuickTime 1.0 Tour, presented by a member of the development team. This tongue-in-cheek video was included on the QuickTime 1.0 CD. Originally a whopping 152 x 116 in size, this was referred to as “postage stamp video” back in 1991. How far we’ve come. Gotta love the portable QuickTime playback container for the DEC PDP 11!

Finally, Klone Killers is short clip also on the QuickTime 1.0 CD. Apple was considering licensing the Mac OS to clone manufacturers by this time, and the QuickTime team had a rather Space Invaders take on the notion. Apparently Steve Jobs felt the same way.

I love finding this stuff!

Anyone who’s been using Macs since the days when SCSI was the primary expansion bus knows that this technology was not something often described as plug-and-play. SCSI did work, but not without challenges. I was reminded of some of these working on a file transfer job this weekend.

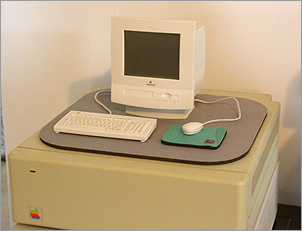

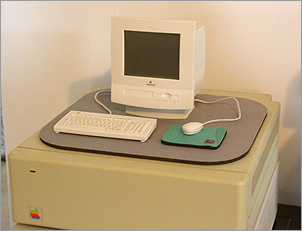

A client sent me a working Macintosh Classic II running System 7.0.1, with several old projects on the internal hard drive. They wanted to get this data transferred and converted to something modern. Since it was bootable and had an external SCSI port, I decided to hookup an external drive to copy the data rather than open the case and pull out the boot disk, or wait for things to sputter along using LocalTalk.

A client sent me a working Macintosh Classic II running System 7.0.1, with several old projects on the internal hard drive. They wanted to get this data transferred and converted to something modern. Since it was bootable and had an external SCSI port, I decided to hookup an external drive to copy the data rather than open the case and pull out the boot disk, or wait for things to sputter along using LocalTalk.

I pulled an 80MB drive from my stack of spares, hooked it up to a SCSI sled (a coverless external case), and connected this to my PowerBook Wallstreet to format the disk. 68k Macs require disks to be formatted in the Mac OS Standard (HFS) filesystem, not the newer Mac OS Extended (HFS+) flavor. The Wallstreet runs Mac OS 9.2.2, and the included disk utility is called Drive Setup. I mounted the old (noisy) transfer drive, selected Mac OS Standard format, and quickly partitioned the disk.

I then spent the next two hours trying to get this hard drive mounted by the Classic. And reminded myself why I like FireWire drives so much better.

SCSI chains require each device on the bus to have a different ID number, and both ends of the chain need to be terminated. On older Macs the internal hard drive was set to SCSI ID 0 and terminated at the motherboard; the system itself used SCSI ID 7. Any external devices need to use ID 1-6, with a terminator. I configured my drive as ID 2, added a passive external terminator, and booted up the Mac.

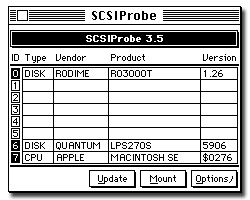

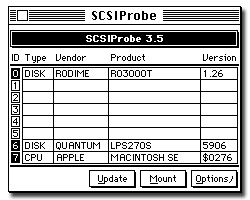

A loud whining sound immediately started emanating from the machine. If I moved the external SCSI cable even slightly the whine changed pitch. Hmmm, that sounded like a motherboard component about to fail. The Mac booted but the drive didn’t appear on the desktop, so I used a floppy disk to load the SCSIProbe control panel and scanned the bus. No external disk found. But the whine continued.

I shut down and swapped the SCSI cable out for another. After a few minutes the whine went away. Such are the risks of old hardware. Still no go on mounting the external drive though, and now SCSIProbe was complaining about a lack of termination on the bus.

I shut down and swapped the SCSI cable out for another. After a few minutes the whine went away. Such are the risks of old hardware. Still no go on mounting the external drive though, and now SCSIProbe was complaining about a lack of termination on the bus.

These classic Macs with their slow SCSI speeds didn’t typically require active termination, but it was the next thing to try. Dug one out of a drawer, and bingo that solved problem number two.

The drive still didn’t mount on the desktop, but SCSIProbe did now see it on the bus – progress. I clicked the Mount button and got an error message that drives larger than 4GB are not supported on 68k Macs. 4GB? This drive is only 80MB. What gives?

I grabbed another 160MB drive from my shelf, connected this to the Classic, and it mounted fine – yay! But this one contained some data I needed to backup first, so I again powered down, hooked the drive up to my Wallstreet, and copied what I needed. When finished I reformatted the disk for good measure, again using Mac OS Standard.

Back on the Classic, I got the same error: can’t read drives larger than 4GB. Huh? It just read that drive. All I did was connect it to the Wallstreet, copy, and… reformat.

Using the Drive Setup utility included with Mac OS 9.2.2.

Another distant memory surfaced: back in the System 7 days (and earlier), Apple used a different utility for formatting disks called Apple HD SC Setup. The name goes back to the very first Mac external hard drive, and the interface is minimal at best, but version 7.3.5 still ran under OS 9. It was worth a try. Launch, click Initialize, wait 15 minutes, and presto: one freshly formatted prehistoric Mac OS hard drive.

I held my breath booting up the Classic again. It chimed, smiled its happy Mac face at me, then quickly and transparently mounted the external drive on the desktop. Finally! Two hours after I started the process – LocalTalk would probably have been done in half the time. But as they say, it was a (Re)Learning Experience.

SCSI Voodoo. Yep. And you thought USB is a headache…

August 2013 has turned out to be a popular month for vintage Macheads to trek over and check out the collection. And notably, the recent visitors are people who weren’t even born when the Mac made its debut!

August 2013 has turned out to be a popular month for vintage Macheads to trek over and check out the collection. And notably, the recent visitors are people who weren’t even born when the Mac made its debut!

This week the world of doll collectors and Macheads got unexpectedly intertwined.

This week the world of doll collectors and Macheads got unexpectedly intertwined. For a short time in the mid 1990s, and too long after it would have made a difference in market share, Apple licensed the Mac OS to third party clone manufacturers. The clones were based on Apple supplied motherboards, with value-added features added by the vendors. The group included PowerComputing, Radius, Umax, SuperMac, Daystar, and Motorola – the latter also one of the manufacturers for the PowerPC CPU.

For a short time in the mid 1990s, and too long after it would have made a difference in market share, Apple licensed the Mac OS to third party clone manufacturers. The clones were based on Apple supplied motherboards, with value-added features added by the vendors. The group included PowerComputing, Radius, Umax, SuperMac, Daystar, and Motorola – the latter also one of the manufacturers for the PowerPC CPU.

A client sent me a working Macintosh Classic II running System 7.0.1, with several old projects on the internal hard drive. They wanted to get this data transferred and converted to something modern. Since it was bootable and had an external SCSI port, I decided to hookup an external drive to copy the data rather than open the case and pull out the boot disk, or wait for things to sputter along using LocalTalk.

A client sent me a working Macintosh Classic II running System 7.0.1, with several old projects on the internal hard drive. They wanted to get this data transferred and converted to something modern. Since it was bootable and had an external SCSI port, I decided to hookup an external drive to copy the data rather than open the case and pull out the boot disk, or wait for things to sputter along using LocalTalk. I shut down and swapped the SCSI cable out for another. After a few minutes the whine went away. Such are the risks of old hardware. Still no go on mounting the external drive though, and now SCSIProbe was complaining about a lack of termination on the bus.

I shut down and swapped the SCSI cable out for another. After a few minutes the whine went away. Such are the risks of old hardware. Still no go on mounting the external drive though, and now SCSIProbe was complaining about a lack of termination on the bus.